We are republishing this article by Friends of Socialist China co-editor Carlos Martinez, which originally appeared in the Morning Star on 11 June 2021. It is the second in a series of articles about the history of the Communist Party of China, which celebrates its centenary on 1 July 2021.

In the period of the Second United Front (1937-45), the Chinese communists won enormous prestige for their leadership of the national defence efforts and for their commitment to improving the lives of the population in the territories under CPC control.

The CPC’s headquarters in Yan’an became a pole of attraction for revolutionary and progressive youth throughout the country.

British academic Graham Hutchings writes, “Yan’an seemed to stand for a new type of society. Visitors, foreign and Chinese, found it brimming with purpose, equality and hope.

“Many students and intellectuals chose to leave areas under the control of a central government they felt lacked a sense of justice, as well as the will to confront the national enemy, for life in the border regions and the communist or ‘progressive’ camp.”

In this period, the CPC leadership devoted some time to theorising the type of society they were trying to build; what the substance of their revolution was.

The results of these debates and discussions are synthesised in Mao’s 1940 pamphlet On New Democracy, which describes the Chinese Revolution as necessarily having two stages: first of New Democracy and then of socialism.

New Democracy was not to be a socialist society, but rather a “democratic republic under the joint dictatorship of all anti-imperialist and anti-feudal people led by the proletariat.”

Political power would be shared by all the anti-imperialist classes: the workers, the peasantry, the petty bourgeoisie and the patriotic national bourgeoisie.

The key elements of this stage of the revolution were to defeat imperialism and to establish national sovereignty, as an essential step on the road to the longer-term goal of building socialism.

How long would this stage last? It would “need quite a long time and cannot be accomplished overnight. We are not utopians and cannot divorce ourselves from the actual conditions confronting us.”

In economic terms, New Democracy would include elements of both socialism and capitalism.

“The republic will neither confiscate capitalist private property in general nor forbid the development of such capitalist production as does not ‘dominate the livelihood of the people’, for China’s economy is still very backward.”

Land reform would be carried out and the activities of private capital would be subjected to heavy regulation.

Perhaps anticipating the “opening up” of four decades later, in conversation with Edgar Snow, Mao envisaged China taking its place within an ever-more globalised world.

“When China really wins her independence, then legitimate foreign trading interests will enjoy more opportunities than ever before.

“The power of production and consumption of 450 million people is not a matter that can remain the exclusive interest of the Chinese, but one that must engage the many nations.”

Following the communist victory in the civil war and the establishment of the People’s Republic of China on October 1, 1949, the new government started building the type of society described in On New Democracy.

Its governance was based on the Common Programme — an interim constitution drawn up by the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, with 662 delegates representing 45 different organisations.

The Common Programme did not call for the immediate establishment of a socialist society and it promised to encourage private business. As Mao had written earlier in the year, “Our present policy is to regulate capitalism and not to destroy it.”

The most important immediate economic change was the comprehensive dismantling of feudalism: the abolition of the rural class system and the distribution of land to the peasantry (a process already well underway in the areas under CPC control).

Land reform resulted in a large agricultural surplus which, along with Soviet support, created the conditions for a rapid state-led industrialisation. Life expectancy, literacy rates and living standards dramatically improved throughout the country.

There was an unprecedented shift in the status of women, who had suffered every oppression and indignity under feudalism. Via a system of “barefoot doctors,” basic medical care was made available to the peasantry.

The New Democracy period only lasted a few years. By 1954, the government was promoting collectivisation in the countryside and shifting private production into state hands. By the time of the Great Leap Forward in 1958, there was no more talk of a slow and cautious road to socialism; the plan now was to “surpass Britain and catch up to America” within 15 years.

The reasons for moving on from New Democracy are complex and contested and reflect a shifting global political environment.

The CPC had envisaged — or at least hoped for — mutually beneficial relations with the West, as is hinted at in the quote above that “legitimate foreign trading interests will enjoy more opportunities than ever before.”

However, by the time of the founding of the PRC, the Cold War was already in full swing. After the defeat of Japan in 1945 and with the outbreak of civil war between the communists and the nationalists, the US came down on the side of the latter, on the basis that Chiang Kai-shek understood the civil war to be “an integral part of the worldwide conflict between communism and capitalism” and was resolutely on the side of capitalism.

The US made its hostility to the People’s Republic manifestly clear from early on. US involvement in the Korean War, starting in June 1950, was to no small degree connected to the West’s determination to “contain” People’s China.

The genocidal force directed against the Korean people — including the repeated threat of nuclear warfare — was also a warning to China’s communists (although the warning was returned with interest, when hundreds of thousands of Chinese volunteers joined hands with their Korean brothers and sisters, rapidly pushing the US-led troops back to the 38th parallel and forcing an effective stalemate).

Soon after the arrival of US troops in Korea, president Truman announced that his government would act to prevent the Chinese island of Taiwan’s incorporation into the PRC, since this would constitute “a threat to the security of the Pacific area and to United States forces performing their lawful and necessary functions in that area.”

Truman ordered the Seventh Fleet of the US Navy into the Taiwan Strait in order to prevent China from liberating it (such, incidentally, are the imperialist origins of the notion of Taiwanese independence).

Along with these acts of physical aggression, the US imposed a total embargo on China, depriving the country of various important materials required for reconstruction.

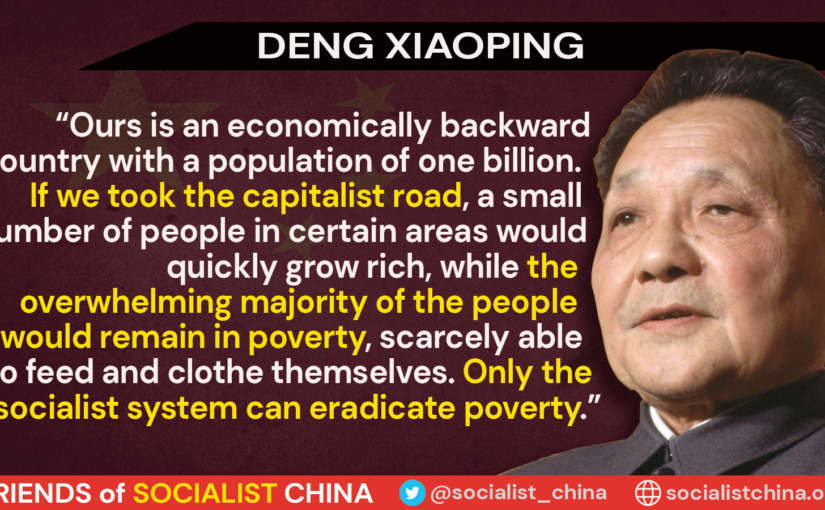

The dangerously hostile external environment made New Democracy less viable. There are parallels here with the Soviet abandonment of the New Economic Policy (NEP) in 1929. Much like New Democracy, the NEP had consisted of a mixed economy, with private business encouraged in order to increase production and enhance productivity.

Introduced in 1921, the NEP proved highly successful, allowing the Soviet Union to recover economically from war whilst minimising internal class conflict.

By the end of the decade, however, new external dangers were emerging and it became clear to the Soviet leadership that the imperialist powers were starting to mobilise for war.

From 1929 the Soviet economy shifted to something like a wartime basis, with near-total centralisation, total state ownership of industry, collectivisation of agriculture and a major focus on heavy industry and military production.

Similarly in China in the mid-1950s, the shifting regional situation contributed to an economic and political shift. Beyond that, there was undoubtedly a subjective factor of the CPC leadership wanting to accelerate the journey to socialism — to “accomplish socialist industrialisation and socialist transformation in 15 years or a little longer,” as Mao put it in 1953.

With the death of Stalin in March 1953 and the gradual deterioration of relations between the CPC and the new Soviet leadership under Nikita Khrushchev, the Chinese came to feel that the Soviets were abandoning the path of revolutionary struggle and that responsibility for blazing a trail in the construction of socialism had fallen to China.

To move from a position of economic and scientific backwardness to becoming an advanced socialist power would require nothing less than a “great leap.”